The centre held its first annual symposium from 4 to 6 June 2025, exploring the theoretical foundations of cultural practices of reparation under this year’s theme, “theory”. Which media, paradigms or concepts allow us to describe these practices? How might they change our many ways of relating to the past, and how might they contribute to new ways of living together in the future? A keynote and eleven presentations approached these questions from a range of disciplinary and cultural perspectives.

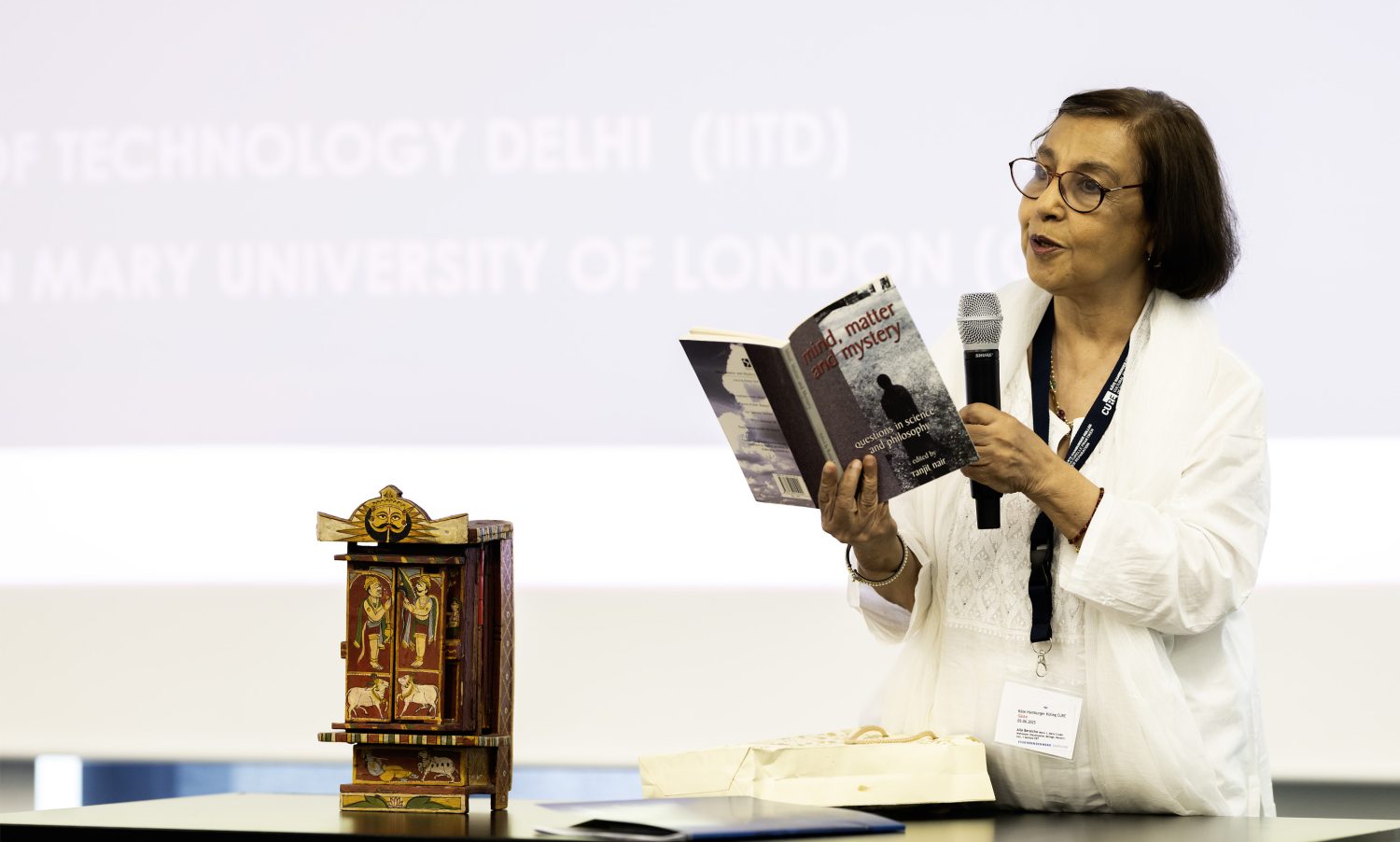

The symposium opened with a keynote by Rukmini Bhaya Nair (Delhi), who explored how structures of communication and conversation can serve as means of repairing postcolonially damaged social relations. Using the Indian kavad – a wooden storytelling box – she demonstrated how narrative nesting can generate awareness of decentred, reparative situations of dialogue.

Pierre Bayard (Paris) introduced the concept of “interventionist criticism”, which not only analyses literary texts but actively alters them – and can thus be seen as a form of literary reparation. Judith Kasper (CURE) engaged with Alfred Sohn-Rethel’s “ideal of the broken”. For Sohn-Rethel, Naples emerges as a place that meets disruption and resistance through practices of bricolage, thus resisting linear historical narratives.

Doris Kolesch (Berlin) examined the relationship between reparation, sound, and voice, drawing on performances by artist Tracie Morris and the project Re:sounding – both of which re-stage so-called lost sounds through a decolonial lens. Ariane Jeßulat (Berlin) showed how musical improvisation can enable social contact and inclusion. As such, the practice of improvisation becomes a model for post-catastrophic solidarity.

Laurent Demanze (Grenoble) asked how literature might have a reparative effect through its engagement with forms of cohabitative living among different actors. Drawing on Lucie Taïeb’s Freshkills and La mer intérieure, he argued that such writing can give voice to forgotten places. Ceyhun Arslan (Istanbul) explored how shifts in dominant spatial imaginaries – understood as “significant geographies” – can expose hegemonic power structures and thus take on reparative force.

Aurélia Kalisky (CURE) offered a critique of theoretical frameworks that distance themselves from reality and retrospectively aestheticise suffering. She called instead for a different approach to memory and for understanding reparation as a preventive practice that refuses the position of academic helplessness. Prevention was also central to the perspective of Hady Ba (Dakar): drawing on examples from the Qur’an and apartheid, he argued that rather than looking backwards, reparation should take the form of proactive strategies to prevent concentrations of power – and with them, the emergence of irreparable harms.

Chris Song (Toronto) explored the possibilities of translation as a reparative practice. Translation here becomes an ethical and decolonial intervention that resists forms of “internal colonisation”. Anselm Crombach (Saarbrücken) introduced “narrative exposure therapy”, a practice in which victims of violence give voice to their traumatic experiences and recontextualise them within the narrative of their lives.

In the concluding talk, Sharon Sliwinski (London, Ontario) showed how dreams, as a social practice, can lay bare colonial power structures and imagine alternative futures. Sliwinski’s account of dreamwork connected theory and art and also circled back to Rukmini Bhaya Nair’s keynote – in both, the linguistic construction of the world plays a key role in enabling reparative approaches to the future.