Outside of academia, the ideals around cultural reparations and restitutions are topical and they should be tailored towards a structural, historic reawakening of Africa’s cultural dignity. The framing of restitution as restorative justice rather than confrontation shows both wisdom and depth of purpose. Reparation and sincere restitution do not mean emptying Western museums; rather, these attempts should be seen as practical approaches to fill African hearts with dignity and memory, which will echo for generations as a moral compass for cultural policy. Call it “European humanism”: these efforts remind us that Africa’s heritage is not lost but reclaiming its rightful place. By “European humanism” or “empathy”, I mean a conviction at the heart of “European humanness” which projects an acceptance of a “wrongdoing” onto the colonised and an effort by colonial powers to make amends.

Unfortunately, Africans during the period of colonial invasions and the looting of their choicest artefacts and identity experienced a form of mental loss that cultural reparations cannot reclaim. A broken mind cannot be mended; its loss irrecoverable and incalculable. Something was taken away from Africans that can never be returned, not even by returning the cultural products/objects that were stolen. Into this emotional chasm, every document concerning reparations and sincere restitution calls for true healing.

However, it seems we are missing an important thread in these discussions about reparations. Despite the intent of Europe’s gesture to repatriate some artefacts which were balkanised and looted/stolen by European colonisers, the approach still raises the question of asymmetrical power relations. This is evident in initiatives such as the establishments of centres for the study of cultural reparations and restitution in Europe, while Africa, the epicentre of these dialectics, stands by as a mere spectator.

Although the efforts at repatriating African stolen artefacts have gained traction, the question of reparation and restitution is almost non-existent in African universities. There are no known associations, centres, institutes, or exchange programmes on reparations being hosted by Europe in any African universities. Even in South Africa – a leader in the continental reparations movement, which encompasses cultural and heritage redress – there is no dedicated centre for cultural reparations in the country.

It is expected that Europe will leverage established academic centres and institutes such as the Centre for Arts, Culture and Humanities at Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Anambra State; the Centre for the Study and Promotion of Cultural Sustainability at the University of Maidugri, Borno State; the Institute of African Culture at the University of Benin, Edo State; and IRUKA Centre for the Study of the Future of Igbo at the Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ebonyi State. Also, at the University of Ibadan, within its Institute of African Studies, there is the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA), a public research institute that promotes and supports research in the social sciences and humanities across West Africa. It fosters collaboration between French (francophone European) and West African scholars, provides grants for research projects, and hosts workshops and seminars. Despite these established institutes and centres, none specifically addresses the reparations dialogue in Africa. This suggests that the continent remains largely unaware of reparations as a subject of academic discourse. To make a meaningful contribution to the reparations movement, the conversation around reparations and restitution must be mutual. Establishing an institute or centre for cultural reparations at a university in West Africa – where actual processes of reparation and restitution are taking place – in the mould of IFRA at the University of Ibadan, would help to foster and galvanise such a mutual exchange and promote a better understanding of the agency of reparations. To realise equitable knowledge exchange, Africa and its intellectuals must be placed at the centre of the entire conversation on reparations and restitution.

Africa should have a voice in sharing the deep feelings and psychological trauma caused by cultural loss, in order to avoid what Adichie (2009) described as “the danger of a single story”. I suggest that the continent should host some of the academic discourses on reparations and restitution, including an exchange programme involving fellows and alumni across Africa, Europe, and the diaspora. Such exchanges would allow for the sharing of firsthand accounts of the true feeling of cultural loss and its accompanying episodes of mental disintegration, which proved both traumatic and psychologically abusive. In this way, discussions on repatriation and restitution can ensure a sincere and sustainable healing process – one that is already being envisioned across Europe. Against this background, let true healing begin – beyond the visual irony and media spectacle.

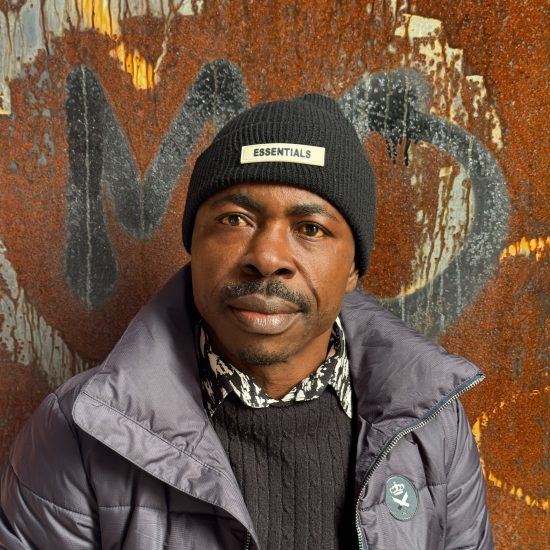

Bernard Orji

BERNARD ORJI. “Of Artistic-Cultural and Emotional Loss, the Ideals of Reparations, and European Humanism”. The Reparation Blog, 5 November 2025. https://cure.uni-saarland.de/en/media-library/blog/of-artistic-cultural-and-emotional-loss/.