A ritual can be defined as a formalised “action” – or as “something” that happens – performed by a group or an individual in a designated space or place, with socially recognised meaning. In Africa, such rituals often constitute not only a belief system but the mainstay of indigenous spirituality and sociocultural life. Among the Igbo of Southeast Nigeria, for instance, key rituals concern rites of passage to different life cycles, involving individuals and communities in times of merriment and sorrow. Ritual is at the core of every ceremony organised to celebrate an achievement or a loss.

However, it has become impossible to find places where these ritual practices are still performed in their pristine form free from the interruptions of Western contestations or intercultural embellishment. The allure of this intrusion has created a gap in the acquisition and transfer of indigenous knowledge. Cultures are permeable and flexible, and societies are influenced by contact with other cultures. Beyond this general dynamic, in Africa in particular, forces of commercialisation and touristification are especially detrimental to indigenous cultural practices. Ossie Onuora Enekwe – the eminent Nigerian author and professor, whose scholarship focused on African ritual and performance – wrote that “a ritual becomes entertainment once it is outside its original context or when the belief that sustains it has lost its potency.”1

Rituals that once served as forms of healing and processes of repair have thus become endangered and more distant in practice, losing their efficacy and agency. At a certain point, Igbo families and communities often experience a need to reconnect to their spirituality through ritual (sacrifice) and restitution. However, with the cultural genocide across Africa, it is difficult to repair the loss of such cultural identity, even when reparations and restitution are being considered by Europeans. The profound and multifaceted impact of losing cultural heritage and the deep emotional trauma that accompanies it are directly linked to themes of colonisation, grief, and artistic expression. This highlights how the theft or erasure of cultural artefacts and practices can lead to a sense of inferiority, a disconnect from history, and to a communal psychological suffering.

When rituals were not yet threatened by colonial influences, it was indigenous knowledge systems that fashioned an understanding of ritual ceremonies, which connected deeply to their own past. This past was built on the experience and significance of the human body – what we might call its phenomenology – and resonated in meanings embedded in Igbo cultural beliefs and practices realised concretely as divination, incantation, ablution, libation, invocation, sacrilege, atonement, sacrifice, consultation, appeasement, a pantheon of divinities and gods, and mediation realised through the human mediatrix (the Chief Priest, the Priestess, and their acolytes). In this sense, Igbo indigenous rituals and their trajectory of development leveraged semiotic tools, widening the scope of mediums by which humans communicate. A multitude of communicative options – signs, gestures, colours, sounds, forms, and symbols, as well as verbalisation – serve to mediate between man and the supernatural or celestial beings.

Even today, in many indigenous Igbo societies, the naming of a child is a ritual tied tenaciously to the belief in the supreme being – Chukwu. In Igbo cosmology, the reverence and deference attributed to this God is profoundly intentional. This is especially evident in how the name of the supreme God in Igbo has become proselytised and has literally transformed naming styles. For instance, Chukwu is the Supreme God; Chineke is the God that creates or the font of creativity. Following from the prefix of Chi as the Supreme God, names reflect God’s virtues, such as Chibueze (God is king), Chidiebere (God is merciful), Chimamanda (My God will never fail), Chidimma (God is good), Chiebuka (God is great), etc. Many names, both traditional and modern, begin with prefixes like “Chi” or “Chukwu” to signify a connection to the divine and spirituality. Hence it is easy to observe the ritualisation of divinity in naming ceremonies in indigenous Igbo societies of Southeast Nigeria. They exemplify how ritual is a major component of rites of passage in Igbo indigenous sociocultural order. Here, there is an upward movement that activates the relevance and significance attached to social status, hierarchy, self-actualisation, and fulfilment.

To understand the workings of indigenous rituals before their annihilation, it further behooves this intervention to situate ritual processes in the context of demonstrable and tangible localities and settings. According to David Eller, one of the most persistent forms of material religious objectification are sacred sites or places. In most, if not all, religious traditions, “place” is deeply important for belief and worship; such a location is not a random space but a space where something is or where something happened (a place of healing and repair).2

In indigenous rituals in Africa, sacred places or operational sites include the shrine, the coven, riverbanks, T-junctions, footpaths, roundabouts, streams, rivers, forests, markets, tombs, men’s and women’s inner chambers in their homes, or what Ottenberg described as a house of men.3 In some instances, trees are consecrated at specific locations only identifiable by community or family members. This site serves as a worship/ritual centre for the community and is kept secret and carefully disguised from unwanted group or non-members of the community/family, lest enemies desecrate it. The tree is the centre of ancestral worship, ritual sacrifices, and ablution, as well as a healing point for all community members. Here, the gods serve as mediatrix and deified ancestors, who are physicalised in masquerades during festivals in honour or celebration of rites of passage in the community. The masks worn by some masquerades are carved from some of these trees and must be properly purified in a cleansing ritual before and after the masquerade outing.

The veneration and deference attached to the presence of masquerades among the living in Igbo cosmology underscores their inscrutability and wonderment in Igbo lore and mores. To further buttress this point, no individual masker or initiate adorns the mask or masquerade costume without a proper ritual of purification or cleansing carried out before and after the masquerade outing.4

However, when things go wrong because of neglect or violation of standing rules, as spelt out in the people’s ordinances or declarations, the community suffers the repercussion through the reactionary intervention of the land (ala). The ala (land) forms the central core of Igbo consciousness. In fact, the totality of Igbo life – its culture and custom – revolves around it.5 The people worship ala, and their food and water come from it. Famine or low agricultural productivity, pestilence, illnesses, and unknown deaths come from human offenses against the gods (earth goddess) of ala, and they usually attract heavy penance and ritual sacrifices, including killing of goats, rams, and cockerels, and the use of many sacrificial objects. The blood of the animal killed is sprinkled around the shrine or location of the ritual to ensure positive intervention and adequate atonement, which attracts total healing for the community.

The ritual associated with blood is not only admissible with animal bloods. In almost every rite of passage of an Igbo child, the blood is spilled as a connection between the child and the earth goddess (ala) on whose benevolence the child grows into maturity. An example will suffice: every male child is circumcised on the eightieth day after birth. The foreskin and the blood are buried in the earth (ala). This act defines perpetual earthly connection with the child and enables the male child to establish a direct connection between the earth, a relationship that can be renewed at any given opportunity.

A further example of ala’s importance to Igbo consciousness is the relationship to one’s dead ancestors. A man connects to his dead ancestors by prayers or by pouring libation using palm-wine or any kind of liquor. Part of this is demonstrated by pouring out part of the drinks on the ground or floor of the man’s house where the dead is buried. The Igbo bury their loved ones in their homes or just around their compounds. Celebrating the dead is part of the ritual processes in Igbo as prayers offered with drinks are heard by the dead and the living enjoys their benevolence through attainment of success in life’s endeavours.

The jubilation and ululation that accompany such successes in life also calls for celebration and another round of ritual process (of acceptance). It becomes a cyclic interventionist supplication overtly acknowledging man’s constant exposure to hubris and offense and thereby seeking endless absolution through restitution. Punishment, penance, sacrifice, atonement, and reward are commensurately dispensed across members of the community.

However, the history of colonialism – as noted above – has interrupted this cycle. So, I dare to ask: how can the loss of identity caused by the disappearance of rituals be repaired?

With Stuart Hall and Homi Bhabha’s ideas of cultural hybridity and third space, we may begin to consider “hybrid rituals” as a form of repair in understanding indigenous identities in modern times. Hybrid rituals as a form of cultural admixture – blending or fusion of different cultural elements – have been observed among the Igbo people. One example is traditional marriage ceremonies, where the use of palm-wine is replaced with Guinness Stout or European wines presented by the bride in a glass cup instead of calabash gourd, while the pouring of libations by the elders now ends with “in Jesus’ name” and the chorus “Amen” has replaced “Ịséé” known with the Igbo. Many instances abound which space cannot permit.

What is crucial here is that indigenous Igbo rituals do not in any way impose their concepts and ideas on foreign religions, rather their flexibility enjoys acculturation or what Chukwuma Okoye identified as cannibalisation seen in Igbo masquerades.6 By this he means that masquerade culture in Igbo society has continued to remain popular and relevant due largely to its disposition to cannibalisation – ripping off, stealing, diluting, and tearing off other cultural artefacts to enrich its visual and kinetic aesthetics. And even if other cultures and religions regard indigenous Igbo rituals as heathen, barbaric, voodoo, or Blackmagic, these thoughts or dispositions cannot declare them to be false, detract from their significance, or negate their existence. The approach, functionality, ideals, and communality of Igbo rituals – their potpourri of visual spectacles and undercurrent meanings – therefore align with a decolonial temperament of true identity, which are efforts towards the conversation being championed by Olúfemi Táíwò in his Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously (2022).7

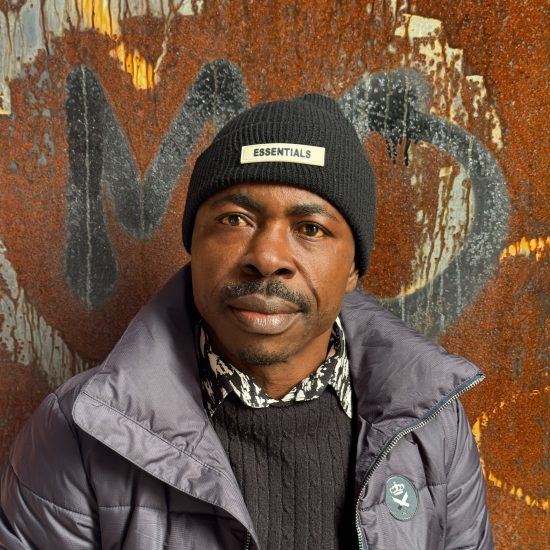

Bernard Eze Orji

1. Ossie Onuora Enekwe, Igbo Masks: The Oneness of Ritual and Theatre (Nigeria Magazine Publication, 1987), 51.

2. Jack David Eller, Introducing Anthropology of Religion: Culture to the Ultimate (Routledge, 2007), 63.

3. Simon Ottenberg, Masked Rituals of Afikpo: The Context of an African Art (University of Washington Press, 1975), 23.

4. Ottenberg, Masked Rituals of Afikpo, 18; Yemi Ogunbiyi, Drama and Theatre in Nigeria: A Critical Source Book (Nigeria Magazine, 1981), 21; Margaret Thompson Drewal, Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency (Indiana University Press, 1992), 45; Bernard Eze Orji, “Interculturality and Hybridity in Okumkpó Masquerade of Akphoa-Afikpo” (MA thesis, University of Ibadan, 2012), 70.

5. Elizabeth Isichei, A History of the Igbo People (Macmillan, 1976), 86.

6. Chukwuma Okoye, “Cannibalization as Popular Tradition in Igbo Masquerade Performance,” Research in African Literatures 41, no. 2 (2010: 19–31, on 20).

7. Olúfemi Táíwò, Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously (Hurst & Company, 2022), 2.

Orji, Bernard Eze. “Igbo Rituals”. Repair: A Glossary of Cultural Practices of Reparation, 20 January 2026. https://cure.uni-saarland.de/en/media-library/glossary/igbo-rituals/.